When we deal with pests on crop lands, we usually stick to a few straightforward strategies. We either try to breed more resistant plants or we spray them with specific and less specific pesticides. Organic farming – while still using some spray-on pesticides – has vowed to reduce their use. And as researchers recently discovered, they might do very well without them.

If you ask farmers that grow both organic and conventional crops, they might share a peculiar observation. Organically farmed crops often have less insect damage despite being sprayed rarely – if at all – with insecticides.

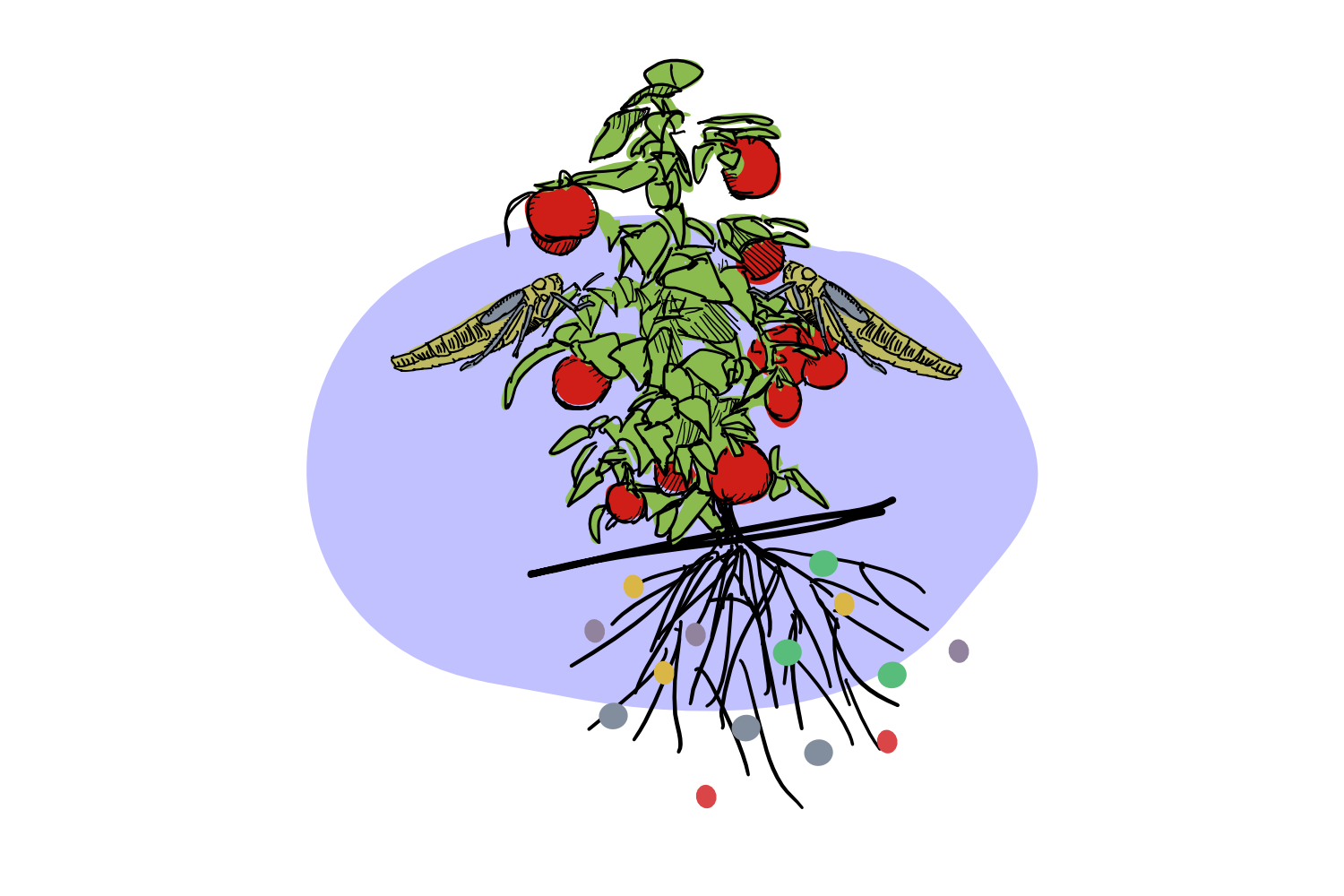

A common theory revolves around the idea of a more robust and diverse ecosystem around the plants. Predatory insects feed on the pests and reduce their numbers while trap crops lure the pests away. But one other factor remained overlooked for a long time: the diversity found not above the soil, but within.

The grad student Robert Blundell and his colleagues from the University of California set out to investigate the effect of the relationship of plants and soil microbes on the resistance of tomatoes against leafhoppers. They collected tomato branches from a number of test farms that used both organic and conventional farming practices. When they presented them as a tasty treat to leafhoppers, the insects preferred the conventionally grown branches. Organically grown plants seemed to be less attractive to the pest insects.

This first observation demanded deeper investigation. The researchers went into the field and counted leafhoppers on tomatoes and saw their lab experiment supported: there were more leafhoppers on conventionally grown tomatoes than on organically grown plants.

The reasons for this phenomenon could be plenty. Nitrogen content in the soil (and therefore in the plant) is a major influencer both on plant fitness and on attractiveness of the plant to insects. As organic farming uses almost no inorganic nitrogen fertilizers, the low-nitrogen content of organic leaves could be a straightforward explanation for leafhopper preference. However, this was not what the researchers observed. Organically grown tomatoes had similar levels of nitrogen in their leaves when compared to conventionally grown plants – which ruled out that explanation.

So the research team turned to the microbes in the soil. They brought samples from the organic and conventional plots to the lab and turned them into a slurry that contained the microbes but not the physical matter. After growing plants on slurries from conventional and organic fields, they could find yet again that leafhoppers preferred conventionally grown tomato plants. However, when they autoclaved the soil, effectively killing all microbes, they saw no difference between the two cultivation methods. The secret seemed to lie in the community of bacteria in the soil.

To understand how the bacteria might influence plant resistance, Blundell and colleagues measured the levels of salicylic acid in the plants. This signalling molecule is known to be involved in plant defence and general pest resistance. They observed increased levels of salicylic acid in the organically grown plants – on soil, in the field and using the lab slurry. They argued that the increase in salicylic acid most likely explains the resistance of organic tomatoes against leafhoppers.

In the past, it was shown that soil microbes can boost the salicylic acid levels in plants, which puts the plants’ immune system into a state of higher alert, ready to fend off pests like leafhoppers. However, the response is specific to only a number of insect species. The leaf chewing larva of the moth Manduca sexta, for example, remained unimpressed by organic growth conditions. Another pest, hemiptera, on the other hand, followed the leafhoppers example and preferred organically grown tomatoes.

The study sheds new light on the often-missed influence of biodiversity in soil on the crops that grow in it. The plant-microbe interactions go much further than what we know from effects like the symbiosis between legumes and mycorrhiza. The combination of biodiversity-retaining practices in organic farming and smart use of pesticides when necessary, combined with fast and efficient modern breeding of resistant crops, might help us to greatly increase the sustainability and robustness of our farming practices in light of growing demands and the global climate crisis.

References

Blundell, R., Schmidt, J.E., Igwe, A. et al. Organic management promotes natural pest control through altered plant resistance to insects. Nat. Plants 6, 483–491 (2020).