Living in a globalised world certainly has its perks – goods and people travel around the globe, and more and more people have access to things deemed unobtainable 100 years ago. But travelling the world with those goods and people are less desirable things, including pathogens. Now, a fungus made its way onto the South American continent, threatening to wipe out the local banana production. So, how bad is it?

The blind fungal passenger has a rather complex name: Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 (TR4). The complexity is necessary, because Fusarium oxysporum is a species with many varieties, a lot of which are harmless or even beneficial soil microbes. Several of them, however, are infectious. The pathogenic varieties enter the plant through the roots and spread through the vascular tissue.

The vascular tissue represents the arteries of a plant. Through it the plant transports water and nutrients, and blockages present a major problem to the plant. We recently talked about air bubbles inducing embolisms which result in the death of the tree. Having fungus growing in the vascular tissue can also lead to a slow end to a plant’s life.

The TR4 variety is an especially mean member of the Fusarium oxysporum species. It is resistant to chemical treatment, lingers for over 40 years in the soil and, worst of all, it infects the commercially most important banana variety – the Cavendish banana.

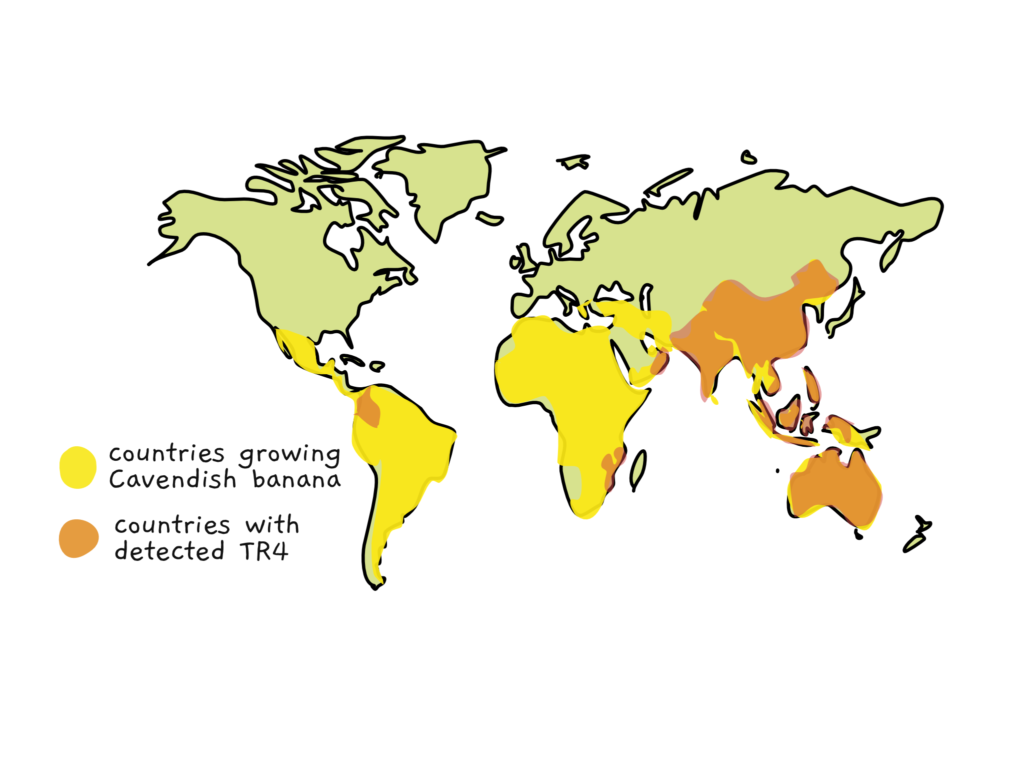

Previously, TR4 has been a big problem in banana producing areas like Australia and Southeast Asia, where it infected banana plantations and led to harvest losses. While it has been already detected on the African continent, Central and South America have remained free of TR4 – that is until now.

Very recently, a lab in Colombia confirmed what banana producers feared: TR4 has reached Colombia, and will likely continue its spread from there. As TR4 is so exceptionally resistant to countermeasures, the only tool available today is quarantine and containment of the infected plantations. Of course, given the fungus’s ability to spread through plant material, soil and water, and the increasing exchange of tools and personnel between plantation, quarantine isn’t always a permanent solution.

So, will we lose our banana for breakfast?

To get an idea about the danger of TR4, we need to look to the past. Before Cavendish became the defining variety of banana, the Gros Michel variety dominated the market. Today, however, it is not commercially grown anywhere in the world. Because of TR1.

As you can guess from the name, TR1 is a fungal race to TR4 and threatened banana plantations in much the same way. Gros Michel plantations were soon overrun by TR1, so farmers changed to the TR1-resistant Cavendish variety.

(Today, Gros Michel lives on in the artificial flavour for banana, but that is a story for another time.)

A loss of Cavendish plantations would be disastrous. And I’m not talking about the loss of banana bread from your fancy coffee shop – banana is a staple crop in many countries and its production is a major economic activity providing millions of people with jobs. A loss of this sector due to TR4 would lead to widespread downstream effects.

So far, TR4’s spread has been pretty slow, and global banana production has in fact increased in the last decades. But T4 is spreading. And this time, we don’t have a replacement variety to take its place if we loose the Cavendish bananas. Normally, an option would be to breed more resistant varieties. But if you’ve ever paid close attention to your morning banana, you might have have noticed that they don’t have seeds. Modern banana varieties are seedless and propagated through clones in tissue culture. While the method is effective for the propagation of a species, it makes crossing and breeding very difficult.

A possible solution could be gene technologies. Researchers around James Dale identified the gene RGA2 as a potential target to make banana resistant against TR4. The gene is present and highly expressed (the plant makes a lot of the protein) in a non-commercial sweet banana variety in Southeast Asia that has some resistance to TR4. In Cavendish, the gene is there, but is very lowly expressed.

The TR4 resistant variety is of no commercial use, unfortunately. It is one of the earliest domesticated banana plants. It marks the beginning of banana breeding and as it often is with the very first version: it is not as great as the varieties that followed. Through hybridisation fruits got larger, lost their seeds and their taste changed.

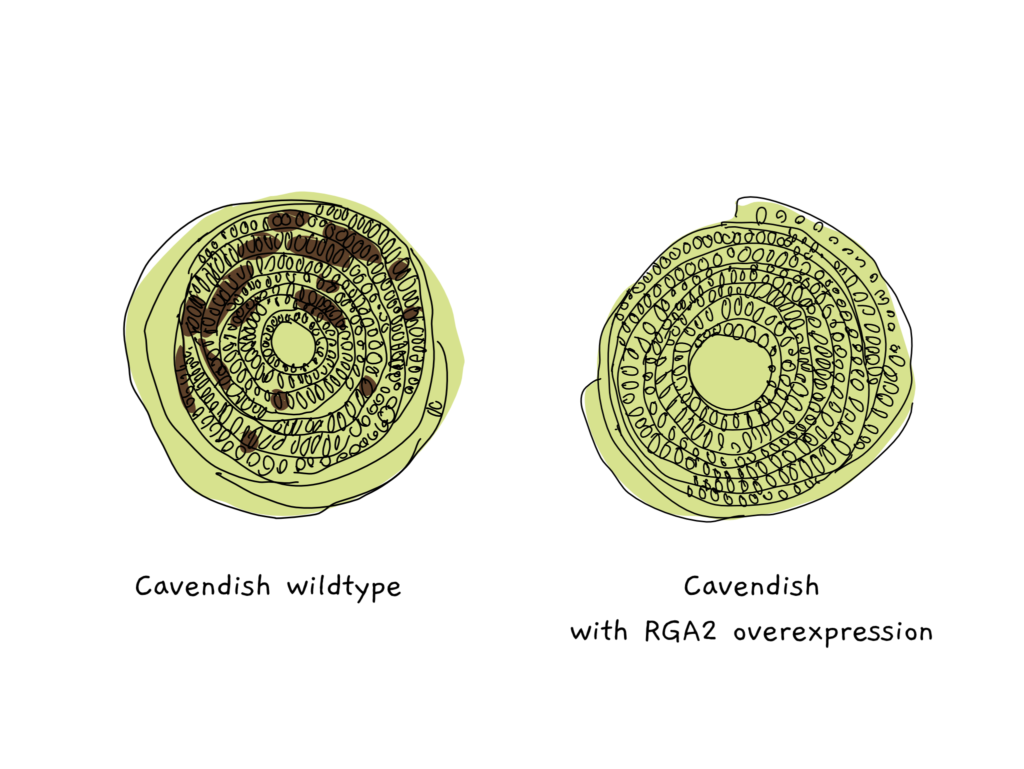

Today, researchers are trying to bring the resistance of the old variety into commercially valuable lines. In a transgenic overexpression experiment, Dale et al. managed to boost expression of RGA2 about tenfold in Cavendish bananas.

The result was a TR4 resistant plant line that could grow even on infected soil, were non-transgenic banana plants perished. The line is currently undergoing extensive field trials to bring it to the market.

At the same time, transgene-free technologies* like genome editing are investigated. As the RGA2 gene exists in Cavendish, it is just a matter of boosting its expression through targeted mutagenesis of its regulatory elements. That sounds simple, but requires extensive knowledge about the sequences and their function.

No matter what technology makes it to the market first, the resulting banana plants might be resistant to TR4… but not resistant to the regulatory system of the EU. Even transgene-free gene edited plants overexpressing the naturally present RGA2 gene would not be legally imported into the EU.

We might be re-entering a time where bananas, in Europe at least, are a luxury.

*depending on the definition of your local country and/or state. We’re using the logical definition of transgene free here. Not the bizarre legal definition that the EU has come up with.

References

This article in nature summarises the current situation quite nicely:

Alarm as devastating banana fungus reaches the Americas (Nature.com)

This article from the guardian was written before the fungus reached South America and gives an overview over the research done on banana resistance.

Science’s search for a super banana (guardian.com)

The research article on transgenic RGA2 overexpression: Dale, J., James, A., Paul, J.-Y., Khanna, H., Smith, M., Peraza-Echeverria, S., … Harding, R. (2017). Transgenic Cavendish bananas with resistance to Fusarium wilt tropical race 4. Nature Communications, 8(1), 1496.