Sometimes all you want for your research is a couple million of your favourite lab rat. No space in the green house? Try a beaker! Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is your guy – in fact, with Chlamy, you’ve got several million guys per millilitre.

This is part III in our series on our favourite lab rats in plant research. We already talked about Arabidopsis and tobacco, two proper, big(ish) plants with leaves and roots and flowers. Sometimes however, you don’t care for plant organs – all you want is a nice, big chloroplast with some cell around it. Sounds like a job for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii!

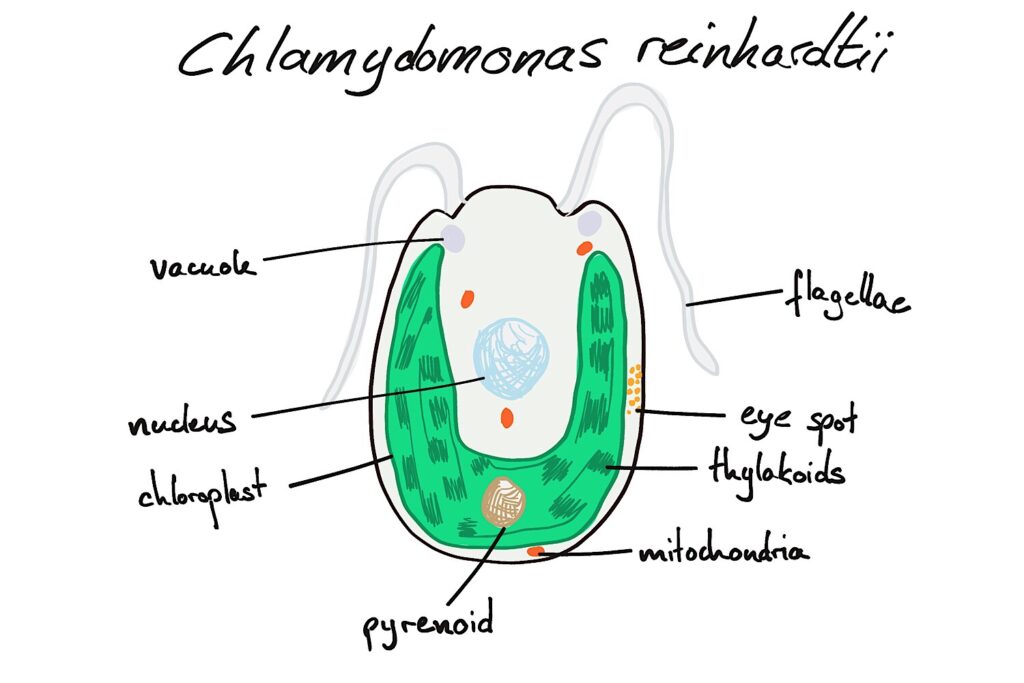

Chlamy, as friends and family call it (don’t confuse it with Chlamydia!) is a unicellular green alga. So ok, not technically a plant. But still used in the plant word as a model for photosynthesising organisms. It is small (about 10 µm), lives in soil and fresh water and can move about with two flagellae. These long antenna like structures work like whips to gracefully propel Chlamy across its habitat.

In the lab, we grow Chlamy in liquid culture which is a fancy word for beakers with watery broth. Being green and plantish, Chlamy can use light to photosynthesize and grow, but it grows a lot quicker when supplemented with the carbon source acetate. In fact, the ability for Chlamy to grow either completely photoautotrophically (using photosynthesis), completely heterotrophically (no light, feeding on acetate) or mixotrophically (you guessed it, with both), is one of it’s important useful features. Being able to grow them on acetate allows them to grow happily, and green-ly even when photosynthesis is disrupted. As we often use knockouts to understand gene function we’re really happy to have Chlamy to take the hit to its electron transport chain.

Fast growth is also a strong plus: Chlamy can grow from single cells to high density cultures of several litres in just a couple of weeks. Not even the sprinter Arabidopsis can compete with that.

When discussing lab rats, us molecular biologists immediately gravitate to the biggest question: which of the genetic compartments (nucleus, plastid or mitochondria, can you transform? Chloroplast and nucleus transformation has long been available for tobacco, while chloroplast development protocols were only recently developed for arabidopsis. With Chlamy? You can do it ALL. Even the mitochondria!

On top of these features, Chlamy has a fairly small nuclear genome. It can be propagated both asexually or sexually (although the latter can be a bit cumbersome), opening it up to genetic studies. It’s also got an ‘eye spot’ that senses light, and with it’s flagella, can be used for studies of movement and phototaxis (light responsive movement).

Having worked with Chlamy however, I have to tell you: it’s not as easy as it seems. Contrary to higher plants that happily take up foreign DNA and keep it relatively stable, Chlamy is a little moody. Transgenic DNA is often quickly silenced: it’s expression is driven to almost zero as your once happily expressing strain returns back to being as boring as wildtype.

On top of that, the Chlamy nuclear genome has an unusually high GC content, which hinder certain basic molecular biology processes. Even doing a simple PCR can be tricker in the algae than in model plants.

Which brings us to the next part: Chlamy’s use in applied biotechnology. Having three main cellular compartments accessible to transformation should – in theory – open up a world of biotechnological possibilities. Drugs made from sun light, new food sources, biofuels! However, the reality so far is that Chlamy is better as a model than an actual productive performer. Its tendency to gene silencing makes it challenging to use, cultures can be easily contaminated with bacterial growth, and its reliance on fresh water makes it less interesting for large scale production where salt water algae are favoured.

Researchers love Chlamy for its large pool of useful talents, but are simultaneously stressed by its weird particularities. It’s like a capable neighbour that has all the tools in his garage but will never shut up about Finnish dog shows he watches all night on cable TV.

Sometimes you’re happy for his help and sometimes you’d rather talk about cats.

References

Check out this (slightly old, but open access!) review, which gives Chlamy the amazing title of ‘Photosynthetic Yeast’: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001233